See, “eku” is “uke” upside down, and this tuning idea combines an upside down ukulele tuning with cello pitches…where the two 4-string groupings overlap the C2 and the G2 strings.

Maybe I should explain…

The idea

I’ve for a while been intrigued by the concept of an idealized tuning, for a single six-stringed instrument, that would allow me the greatest general-purpose flexibility to do all the very different sorts of things that I (think I) want to do. So, for example, I want at least one four-string grouping on which I can lean for scale work and primary three- and four-string chord shapes; for me that means ‘fifths’…but I’d also like to have access to the standard tuning’s top three intervals, for some of those closer chord voicings, and the minor triad/relative major triads that those open strings represent (D-G-B is G major, and G-B-E is its relative E minor). Similarly, I like bass strings to be spread out so that chords don’t sound muddy…and yet as I develop my interest in fingerstyle, the idea of having the bass strings closer together in order to have more comfortably available bass notes is also intriguing. (Oh, this sort of thing goes on, I assure you.)

And then, just a few days ago, I picked up my daughter’s ukulele, and had an epiphany.

How this started

When I picked up Sabre’s uke, I wasn’t thinking about general-purpose tunings. I wanted to re-familiarize myself with standard-tuning guitar intervals (for strings 1-4) in order to work with someone who had been expressing interest in learning chords from me. So, I sat down to work out basic triads and sevenths, using a “method” derived from an exercise I first learned from Hideyo Moriya of the California Guitar Trio. All well and good, and I eventually got to the point of playing the diatonic triads of the key of C, up the scale, chord melody style.

Now…I have also long wondered, about the ukulele tuning: why is the fourth string (the G note, in the “C tuning” of G-C-E-A) pitched higher than the third string’s C note? Almost all guitar tunings ascend in pitch from the sixth string to the first, and it would seem counterintuitive to go against that idea–and yet here we have this ukulele thing. Seriously, why?

And then, in trying to deduce a couple of the more challenging fingerings presented, I suddenly really looked at the strings as two groups of three, rather than only at one group of four. I do this all the time with guitar and mandolin; maybe that’s where the idea came from, but suddenly something popped right out at me, and I realized that by playing the diatonic triads through the scale as three-string groups, I could switch three-string groups at will, and wind up with comfortable fingerings, while retaining the consistent ascending treble note. That is: the sound of the treble note ascending through the scale could be sent back and forth between the first and fourth string along the way, depending on which fingering was more comfortable or convenient. And this was quite a whoa! moment.

Enough so, in fact that it kicked my “think it through to the logical end” tendency into gear, and I suddenly saw it paired with four strings in fifths…if it were done upside-down.

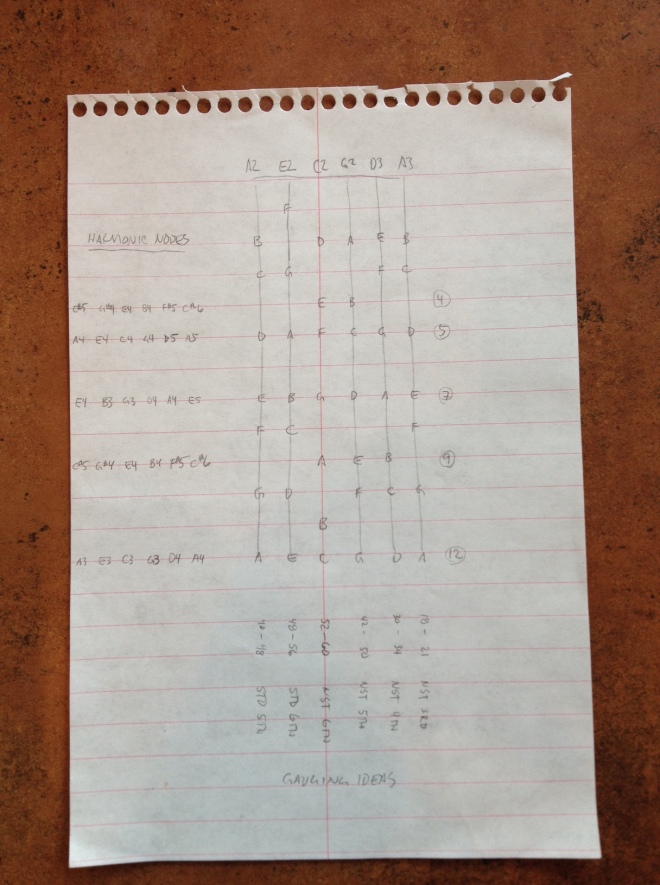

Paperwork followed:

Yes, yes, this idea just might work. I figured I’d chew on it a few days and then string something up. Ha! Strings went on within the day.

What I did (alternate title: I are a musical redneck)

I probably should not have chosen the Ovation for the first experiment, but I wanted familiarity, comfort, and a real acoustic body. Given the realities of home life right now, with the kids at ages 7, 4, and 1, the quickness of the string change was also an appeal of the Ovation. And so I strung it up thus:

A2 – E2 – C2 – G2 – D3 – A3

Strings 3-4-5-6, then (G2-C2-E2-A2), are the upside-down ukulele intervals, and strings 4-3-2-1 are from the Guitar Craft standard tuning that I first learned to play a guitar on.

I used strings I had laying around. Gauges are approximate, but fairly reasonable. At these pitches, all six strings are going to be wound instead of plain, but since I didn’t have ready access to an appropriate steel string for the A3, I thought I’d try the expedient of using a nylon (a 3rd string .040 from a classical set) for that outboard A. This arrangement has worked well on my acoustic fretless guitar, which currently wears three flatwound steel basses and three plain nylon trebles.

What intrigues me

The fifths are there. All that work with chord inversions on the Guitar Craft guitar and mandolin, means that I can already cover basic chords all up and down the board, either in 3-string or 4-string configurations, as needed. I’m comfortable with scales in fifths, and even with “only” four strings to work with, two octaves are readily available in a single hand position.

The standard tuning is there. Strings 6-5-4 are the minor triad of the standard tuning’s top three strings (just Am instead of Em, open, voiced with root on top and 3rd in bass). Strings 5-4-3 are the relative major (C, with root in bass and 3rd on top). Closely-voiced chords are available, as are standard-tuning scale runs; the fact that it is upside-down is less important to me, for whom standard tuning is really an alternate tuning.

The ukulele inversion is there. With the third and sixth strings pitched just a whole tone apart, as are the uke’s first and fourth strings, the hot-swappable treble note promises to open up fingerings. The upside-down-ness of the ukulele intervals means both that bass notes in fingerstyle should be more closely available to some available finger, and also that several general chord shapes are very similar to the shapes of the chords on the fifths side (e.g., in general I am accustomed to workhorse chord shapes that “slant” from bass side to treble side, as the notes go up the neck, whereas many of the standard tuning’s shapes “slant” the opposite direction.

Big strings mean rich harmonics. Not only that, but with these pitches, the harmonic nodes are pretty interesting. One of the things I like about the DADGAD tuning–specifically, the “-DGAD” part of it–is that the basic harmonic nodes contain a complete D scale in them. This doesn’t quite have that, but it does have some rich partial sequences of a few different nastier scales, even before considering partial-capoing.

The idea should scale up and down in pitch. The overall range of the tuning is a minor third smaller than the two-octave range of EADGBE or DADGAD, and a minor seventh smaller than the Guitar Craft tuning, CGDAEG. The flip side is that there’s more overlap, and the whole tuning can be scaled up or down pretty broadly without running out of string-gauge headroom. In a practical sense, at a guitar’s scale length, pitching the low note at C2 is probably at the bottom of the available range; one could take the whole tuning up a perfect fifth, wherein the low note would be G2, and still have the high note be pitched comfortably at the standard tuning’s high E4. At the high G4 of the Guitar Craft tuning, the low note would be Bb2, implying that we’ve got a minor seventh of overall adjustment range to work with. Flexible!

Initial drawbacks

A little muddy. One of the things I’d wondered about, when papering through this idea initially, was whether the “uke” intervals might be noticeably muddy down low, with chords voiced so closely. One of the things I really like about the fifths tunings that are my “home base” is that the chords are very spread out; even the interior notes usually sound pretty distinct.

And, at least last night, during a very short initial stint in the hands, it seems that the mud consideration is at least somewhat valid. Single notes are just fine, and I’m intrigued about the idea of having bass notes comfortably available for the left hand during fingerstyle improv and solo arrangements, but the “hot-swappable” aspect of the ukulele’s first and fourth strings, for voice leading, doesn’t seem nearly as compelling so far down into the bass range. (Right now, with brand-new, bronze-wound strings, I’m also fighting a bit with the limitations of my own fingerstyle technique, in terms of string noise and clarity of delivery. At some point I may want to see if flatwounds give me a better sound.) Again, if this experiment gains momentum, I’d be tempted to try a higher range for the tuning: maybe up a fifth across the board, which should be well within the possibilities of string gaugery.

Nuts. And saddles. Reorganizing the strings in this way, and especially using a nylon for the treble A, is…well, let’s just say it’s a bit out of spec. Here is where one can really appreciate the brilliance of designers like Rick Toone, whose adjustable nut and integrated bridge/tuning system alone can put one of his instruments on a musician’s bucket list. (And it makes me pine to do a new instrument build myself…)

So, on the Ovation at least, the apparent action of the fourth string, which is now a .059 gauge low C2, is sky-high in slots cut for a .030-.032 D3 an octave higher. Even more absurd is the new first string; a .040-gauge plain nylon sits in (well…mostly atop) slots cut for a .009-013 plain steel string. And the punchline is that the first-string tuner on the Ovation pulls that string distinctly outboard in its slot. Now, don’t ask me how I know this, but did you know that the sound of a first string jumping its nut slot, and diving over the side of the fingerboard, really isn’t all that musical? Because it’s not. And so then I put points back on my Redneck Musician card by securing the first string to the second and third strings, just behind the nut…with a twist-tie. For an extra two points on the card, I offer in my defense the classic Redneck Motto: “Hey, it works, dunnit?”

Anyway, as a workaround, if I wind up liking this experiment, I may well see about switching out nuts and saddles for the tuning. The SoloEtte, with its zero fret and very forgiving “saddle slots”, might also be a viable option.

Now, to experiment!

The whole point of all this, of course, was to experiment, and now that the strings are settling in (especially that nylon, sheesh), it’s time to do that. I’m pretty excited about the possibles, but we’ll see how it goes!